From whiskey river:

A Word on Statistics

Out of every hundred people,

those who always know better:

fifty-two.Unsure of every step:

almost all the rest.Ready to help,

if it doesn’t take long:

forty-nine.Always good,

because they cannot be otherwise:

four — well, maybe five.Able to admire without envy:

eighteen.Led to error

by youth (which passes):

sixty, plus or minus.Those not to be messed with:

four-and-forty.Living in constant fear

of someone or something:

seventy-seven.Capable of happiness:

twenty-some-odd at most.Harmless alone,

turning savage in crowds:

more than half, for sure.Cruel

when forced by circumstances:

it’s better not to know,

not even approximately.Wise in hindsight:

not many more

than wise in foresight.Getting nothing out of life except things:

thirty

(though I would like to be wrong).Balled up in pain

and without a flashlight in the dark:

eighty-three, sooner or later.Those who are just:

quite a few, thirty-five.But if it takes effort to understand:

three.Worthy of empathy:

ninety-nine.Mortal:

one hundred out of one hundred —

a figure that has never varied yet.

(Wislawa Szymborska; translated from the Polish by Joanna Trzeciak [source])

…and:

One Hundred and Eighty Degrees

Have you considered the possibility

that everything you believe is wrong,

not merely off a bit, but totally wrong,

nothing like things as they really are?If you’ve done this, you know how durably fragile

those phantoms we hold in our heads are,

those wisps of thought that people die and kill for,

betray lovers for, give up lifelong friendships for.If you’ve not done this, you probably don’t understand this poem,

or think it’s not even a poem, but a bit of opaque nonsense,

occupying too much of your day’s time,

so you probably should stop reading it here, now.But if you’ve arrived at this line,

maybe, just maybe, you’re open to that possibility,

the possibility of being absolutely completely wrong,

about everything that matters.How different the world seems then:

everyone who was your enemy is your friend,

everything you hated, you now love,

and everything you love slips through your fingers like sand.

(Federico Moramarco)

Not from whiskey river:

[The following excerpt comes from an article, “The Mountains of Pi,” in The New Yorker of March 2, 1992. The article profiled two brothers, Gregory and David Chudnovsky, who had dedicated years of their life — and pretty much all of their New York apartment — to building a sprawling supercomputer (which they named “m zero”) with only a single real purpose: to calculate the value of pi… exactly. (Gregory Chudnovsky suffered from myasthenia gravis, which largely confined him to bed.)][The Chudnovskys eventually gave up the hunt for “exact pi,” says a page at the PBS Nova site, after computing it to over eight billion decimal places. Later, in 1999, a mathematician in Japan ran the streak up to 200 billion decimal places. Wikipedia reports that “practically, a physicist needs only 39 digits of Pi to make a circle the size of the observable universe accurate to one atom of hydrogen.”]The brothers have lately been using m zero to explore the number pi. Pi, which is denoted by the Greek letter Π, is the most famous ratio in mathematics, and is one of the most ancient numbers known to humanity. Pi is approximately 3.14 — the number of times that a circle’s diameter will fit around the circle…

Pi goes on forever, and can’t be calculated to perfect precision: 3.1415926535897932384626433832795028841971693993751… This is known as the decimal expansion of pi. It is a bloody mess. No apparent pattern emerges in the succession of digits. The digits of pi march to infinity in a predestined yet unfathomable code: they do not repeat periodically, seeming to pop up by blind chance, lacking any perceivable order, rule, reason, or design — “random” integers, ad infinitum. If a deep and beautiful design hides in the digits of pi, no one knows what it is, and no one has ever been able to see it by staring at the digits. Among mathematicians, there is a nearly universal feeling that it will never be possible, in principle, for an inhabitant of our finite universe to discover the system in the digits of pi. But for the present, if you want to attempt it, you need a supercomputer to probe the endless scrap of leftover pi.

Before the Chudnovsky brothers built m zero, Gregory had to derive pi over the telephone network while lying in bed. It was inconvenient. Tapping at a small keyboard, which he sets on the blankets of his bed, he stares at a computer display screen on one of the bookshelves beside his bed. The keyboard and the screen are connected to Internet, a network that leads Gregory through cyberspace into the heart of a Cray somewhere else in the United States. He calls up a Cray through Internet and programs the machine to make an approximation of pi. The job begins to run, the Cray trying to estimate the number of times that the diameter of a circle goes around the periphery, and Gregory sits back on his pillows and waits, watching messages from the Cray flow across his display screen. He eats dinner with his wife and his mother and then, back in bed, he takes up a legal pad and a red felt-tip pen and plays with number theory, trying to discover hidden properties of numbers. Meanwhile, the Cray is reaching toward pi at a rate of a hundred million operations per second. Gregory dozes beside his computer screen. Once in a while, he asks the Cray how things are going, and the Cray replies that the job is still active. Night passes, the Cray running deep toward pi. Unfortunately, since the exact ratio of the circle’s circumference to its diameter dwells at infinity, the Cray has not even begun to pinpoint pi.

Abruptly, a message appears on Gregory’s screen:

LINE IS DISCONNECTED.

“What the hell is going on?” Gregory exclaims. It seems that the Cray has hung up the phone, and may have crashed.

Once again, pi has demonstrated its ability to give a supercomputer a heart attack.

…and:

ATLANTA — With more than four such deaths occurring over the past seven years, safety advocates are once again concerned about fatalities resulting from falling down a laundry chute and breaking one’s neck, an accident that is still among the top 600,000 killers of Americans.

Although other deadly mishaps have increased during the first half of 2008 — most notably shooting oneself in the head after mistaking a handgun for a telephone, which jumped four spots to the No. 548,219 most common cause of death — Dr. Lawrence Dunn, a public health expert and spokesperson for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cautioned that citizens should remain aware of laundry chute-related fatalities.

(The Onion, June 20, 2008; excerpt from an article headlined “Falling Down Laundry Chute And Breaking Neck Remains America’s No. 548,221 Killer”)

Of all the songs about numbers I might have referenced in this post… I thought of “One (Is the Loneliest Number)” by Three Dog Night. (Hmm. I wonder how many bands have a number in their names… the Dave Clark Five; We Five; 10,000 Maniacs; arguably U2… I feel a playlist coming on!) I thought of “One” from A Chorus Line… “Land of a Thousand Dances”… “Nothing Compares 2 U”… “In the Year 2525″… “Love Potion #9″…

(Oh, heck, let’s just check this list.)

And then I thought of songs with phone numbers in the title… and then I was lost. Because I could think of only two off the top of my head — and only one which I needed to drive out of my head, by passing it on to you. :) (By the way, a fun page on this subject is this 2006 blog post by Russell Shaw, in his “IP Telephony” column at the ZDNet site. Headline: “Let’s have fun with old songs about phones — do they still hold up in 2006?”)

You’re welcome!

_________________________________

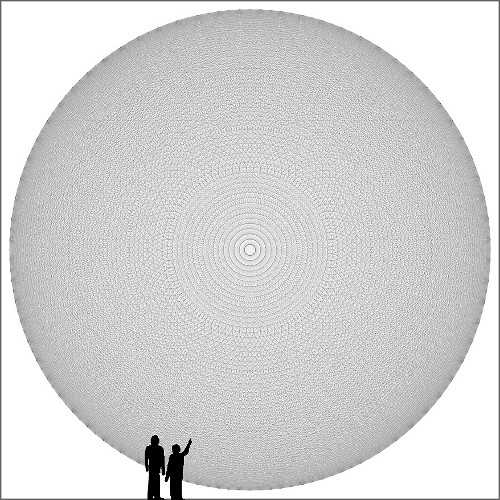

Note: Image at the top of this post is called “Packing Peanuts, 2009,” by artist Chris Jordan. Jordan’s “Running the Numbers: An American Self-Portrait” project assembles, in each work, thousands — even millions — of tiny photographs of some object; the work as a whole represents a statistic about that object. “Packing Peanuts, 2009″ — which at full size is 60″ x 80” — “depicts 166,000 packing peanuts, equal to the number of overnight packages shipped by air in the U.S. every hour.” For a blow-up showing some of the packing peanuts at their actual size, click on the image above. More examples (some quite staggering) can be viewed at Jordan’s site.

Jules says

I love those opening poems. You are one of my favorite poetry sources.

I could look at Jordan’s site all day. Did you see the 32,000 Barbies? Eek… And “Constitution”: Wow.

John says

Jules: On poetry sources… takes one to know one!

Elsewhere on Jordan’s site, he’s got a “Running the Numbers II: Portraits of global culture” exhibit, too — in which he expands his data set beyond the US borders.

And if you want to see something awe-inspiring, there’s this, called “E Pluribus Unum”:

Obviously a mandala of some sort, right? (The human figures are included to provide a sense of the work’s scale.) But when you zoom waaaaaay in, you see “the names of one million organizations around the world that are devoted to peace, environmental stewardship, social justice, and the preservation of diverse and indigenous culture.” (Here are some details.)

marta says

I don’t have anything intelligent to say except that I like the poems and the mandala.

This just made me think of an episode of Torchwood (I know, I know). Anyway, a character shuts down the computerized security system with a poem by Emily Dickinson. At the almost too late moment, the other characters realize that the way to reverse the shut down is with the ISBN on the back of the book the poem is from.

recaptcha: behoove program

Yes. The program behooves me.

John says

marta: You keep telling me these cool things about Torchwood, and Jules keeps telling me cool things about Deadwood. Somehow I continue to miss things whose names end in “-wood.” Maybe has to do with unpleasant experiences in 7th- and 8th-grade shop class.