[Video: “Sailing to Philadelphia,” by Mark Knopfler (performed with James Taylor) (lyrics)]

From whiskey river:

Desire is never on the map

it’s that unnamed lake you found

once, driving a gravel road, not

where you thought you were going,

fast, window down, hair

loose to the dry wind,

bare foot pressing metal,

soft feathers of cottonwood

drift through, maple seed

spinning in its wild gyre.

Bugs spatter on the windshield

in Rorschach you want to

read like tea leaves, imagine

you might learn how you’ve

come to this road, which

left turn at midnight, which

wrong side of town.Then there it is before you,

glittering pure and cold and

suddenly you want

that stone-skipping ache

more than your life, even

knowing how the cold water

makes each hair stand on end

as you enter, one foot at a time

sand crumbling underfoot,

the delicious submersion,

as you slip the laws of

surface tension, gravity…and so it is you push off from shore,

not caring, this lake, as you knew

the moment you saw it,

has no bottom.

(Holly J. Hughes [source])

…and:

Going home does not come naturally to me. If my father’s medium was silence, mine had tended to be escape. But there’s no future in escape because the world is round. So the faster you run away, the faster you end up, right back where you started, face to face with whatever you were running from in the first place. Your worst fears, they’re always the most patient. They’ll wait up for you. That’s what makes them the worst.

(Holly J. Hughes)

Not from whiskey river:

Getting Used to Your Name

After you’ve learned to walk,

Tell one thing from another,

Your first care as a child

Is to get used to your name.

What is it?

They keep asking you.

You hesitate, stammer,

And when you start to give a fluent answer

Your name’s no longer a problem.When you start to forget your name,

It’s very serious.

But don’t despair,

An interval will set in.And soon after your death,

When the mist rises from your eyes,

And you begin to find your way

In the everlasting darkness,

Your first care (long forgotten,

Long since buried with you)

Is to get used to your name.

You’re called — just as arbitrarily —

Dandelion, cowslip, cornel,

Blackbird, chaffinch, turtle dove,

Costmary, zephyr — or all these together.

And when you nod, to show you’ve got it,

Everything’s all right:

The earth, almost round, may spin

Like a top among stars.

(Marin Sorescu, translated by Gabriela Dragnea, Stuart Friebert, and Adriana Varga [source])

…and:

Palimpsests

In most fiction, the aim is to convey the reader to actual and imaginary places, often a mix of the two; and if such places are rendered vividly enough — readers often filling in the blanks to heighten the illusion — then the reader’s memory of a novel is closely linked to the contours of the novel’s places. Miss Lonelyhearts’s room, Bloom’s Phoenix Park, the cheap motels along the highways Humbert Humbert travels, Hemingway’s boat — scores of such places make up the maps of our reading.

But poets are exempt from the duties of social realism, including the credible rendering of place. If poems lead us anywhere beyond their own endings, they lead us into the consciousness of the poet, a map, you might say, of the poet’s intelligence, feeling, perception, intuition, and mannerisms.

When one poet reads another poet, it is like one explorer studying the maps of a predecessor. If the complete works of a poet are a world map of his own making, then to be influenced by another poet is to have the map of his writing placed over your own. Every time another strong influence is experienced, another map is placed on top of a growing pile of maps, which adds up to a weight of influence. And then, if the poet is lucky enough, he discovers his own way of writing, and at that point all the accumulated maps of his reading become transparencies, through which we look into the palimpsest of the new poet’s psyche. Voila!

(Billy Collins [source])

…and:

Take a Left at My Mailbox

Cross Sierra Vista and enter the cul-de-sac

Where the pavement ends

Cross over and down into the acequia full of trash

Where a sodden quilt lies in the middle of where

Stream once moved sand

In eddies. The homeless camp

Disintegrates, only one mattress left

And I’m lecturing my daughter

Who steps back to photograph it

“Don’t come here alone,”

And she retorts: “I have since I was eight,” and then

“It’s so peaceful here, but

I hate the fence.”

This is no arroyo cut by rain

But a remnant of man, an irrigation ditch

Now watering detritus, the leftover, cast off, plastic bags, and worse.

From here you can cut

Up behind the Indian School

Past the transformer I didn’t even know was there

And come our where there once were tracks,

Now just the runners half-buried in soil.

It’s Baca Street! We’re back

In the neighborhood where my daughter

Immediately becomes lost.

“I don’t get straight streets,” she says.

My money’s good here, I buy two cups of foamy chai

And look in her face, turning from girl to woman

And want to construct

My map of the lost.

(Miriam Sagan [source])

…and (from the work which inspired Mark Knopfler’s song):

The Line makes itself felt,— thro’ some Energy unknown, ever are we haunted by that Edge so precise, so near. In the Dark, one never knows. Of course I am seeking the Warrior Path, imagining myself an heroick Scout. We all feel it Looming, even when we’re awake, out there ahead someplace, the way you come to feel a River or Creek ahead, before anything else,— sound, sky, vegetation,— may have announced it. Perhaps ’tis the very deep sub-audible Hum of its Traffic that we feel with an equally undiscover’d part of the Sensorium,— does it lie but over the next Ridge? the one after that? We have mileage Estimates from Rangers and Runners, yet for as long as its Distance from the Post Mark’d West remains unmeasur’d, nor is yet recorded as Fact, may it remain, a-shimmer, among the few final Pages of its Life as Fiction.

(Thomas Pynchon [source])

s.o.m.e. one's brudder says

Ah…..Sailing to Philadelphia such a fine album and marvelously inspired by Mr. Pynchon’s epic tale (does he do any other kind?) of Mssrs. Mason and Dixon. Would that I could actually find a way to keep the necessary mind set to trudge through his prose for this story, of which I am deeply fascinated. Alas, this passage reminds me why I have never managed to complete that trek. I can not hold that 18th Century mindset long enought to traverse/survey/navigate the 1,000 or so pages in anything resembling a straight shot. Sigh….maybe another summer effort awaits.

Curiously, you’ve also managed to link one of my favorite musical compositions to one of my favorite Urban Planning tomes and theories, possibly unknowingly. The Palimpsest as a virtuous metaphor for all Great City Plans as set out in “Design of Cities” by the great urban planner, Edmund Bacon. Yes, that Edmund Bacon, who (after Mr. Franklin, of course) was probably the best planner of one of the best city plans in America – Philadelphia. And only one degree of separation from his son, Kevin Bacon. Yes, that Kevin Bacon.

Hope your mapping relates to your Christmas gifting…

John says

I had no idea who Edmund Bacon was. But your comment sent me looking for him. (Here‘s his NYT obituary, from 2005.) Wikipedia in turn sent me to the December 24, 1965, issue of Life Magazine. Wonder if that issue somehow worked on your little 9-year-old subconscious?

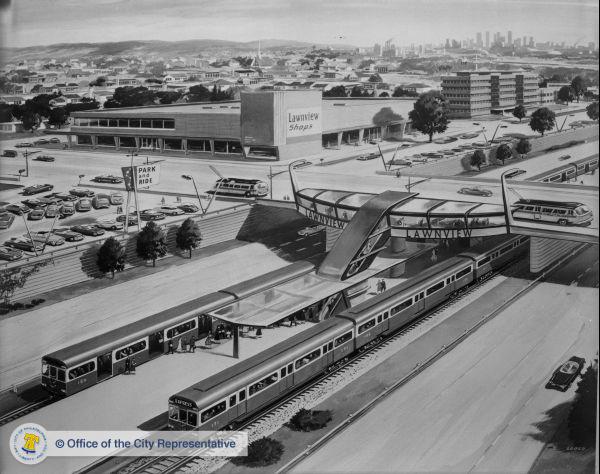

This item from a site about Philadelphia history highlights some of his great ideas that never quite made it through, for one reason or another. This sample image from that page suggests one of those World of Tomorrow visions that put stars in everybody’s eyes back then:

As it happens, I did use one of my Christmas gifts to pick up a copy of the only Pynchon I still didn’t have. But it was Against the Day, not Mason & Dixon. (And it’s the only one not on my bookshelf, but in the Kindle. :))