[Previous Chapter] [Table of Contents/Overview] [Next Chapter]

Gabe knew, by now, he had little chance of returning productively to the darkroom for the rest of the afternoon and evening. He was a little hungry, not remotely famished (and not at all sure he saw the point in eating, maybe ever again). But he told the Lanes of a WorldKitchen a few blocks away which offered good delivery service; it specialized in Kazakh and Samoan cuisines, as well as the rest of the chain’s full menu. If they wanted, they should feel free to order something and have it brought here, on Gabe’s tab. (Later, he’d think how funny that must have sounded — offering to pay a fast-food check for Matthew freaking Burghar‘s daughter and son-in-law.)

Gabe knew, by now, he had little chance of returning productively to the darkroom for the rest of the afternoon and evening. He was a little hungry, not remotely famished (and not at all sure he saw the point in eating, maybe ever again). But he told the Lanes of a WorldKitchen a few blocks away which offered good delivery service; it specialized in Kazakh and Samoan cuisines, as well as the rest of the chain’s full menu. If they wanted, they should feel free to order something and have it brought here, on Gabe’s tab. (Later, he’d think how funny that must have sounded — offering to pay a fast-food check for Matthew freaking Burghar‘s daughter and son-in-law.)

Then, on the pretext of cleaning up some chemicals he’d left open, he went downstairs to the basement and into the darkroom. There he switched on the safelight, extinguished the overhead CCFLs, and sat on the stool in the murky half-light to gather his thoughts.

By the time the doorbell rang — the WorldKitchen delivery — he’d returned upstairs, made vague, forgettable small talk with the Lanes, and sharpened his questions. The tins of darkroom chemicals downstairs remained open.

—-

They’d moved to the dining-room table, Gabe seated at the head — his back to the window, the gray and suddenly treacherous sky — and the Lanes next to each other on one side of the table, to his right. Four foamboard takeout boxes (contents: the day’s WorldKitchen Sampler Platter) were scattered about, loosely lidded, on the tabletop. Eldon’s plate of food, like Gabe’s own, was and would remain untouched; maybe out of politeness, Adrienne had eaten most of a tiny sample from each of the boxes. Across the surface of her white porcelain plate, a smear of dark sauce seemed to have streaked from left to right.

Kali, thought Gabe. He took a drink of his unsweetened iced tea, and rolled the cold glass briefly against his forehead before beginning.

“So. I’ve got a ton of questions, which I guess you’ll answer at some point if I haven’t already asked you to leave. But I’ve got two big ones that I really, really want answers to sooner rather than later. I’m not sure which to ask first.”

Eldon looked at Adrienne, who had to turn her head to look back at him but somehow knew to do so. Naturally synchronized, Gabe thought. He remembered what that felt like — that little tug of an invisible string from someone even across a big roomful of other people. Now, he guessed, he wouldn’t feel it again—

Adrienne spoke. “You want to know what anyone in the world could possibly do about something like Kali. And you want to know: why you?”

“Yeah! I mean, if this whole solar system’s gonna be wiped out, then how does somebody, least of all me, save the world?”

Eldon again startled Gabe with laughter. “‘Save the world.’ I like that. No, Gabe. There’s no saving the world. Or not exactly—”

“El,” said Adrienne. “Let’s do it the other way round.” She turned back to Gabe. “Let’s take the ‘Why Gabe?’ question first.”

She took from a pocket another of the little black-disk projectors, and placed it on the table next to the little box of still steaming dao-fruit-and-sausage salad. She didn’t turn the projector on right away.

“How much do you know about my mother, Gabe?”

He thought, immediately, what practically everyone else thought when the name Dolly Magaziner Burghar came up: Nutty blonde hippie chick. He wasn’t about to say that, though.

“Well, um, I know she and your father were very much in love. And she was a, well, a philanthropist I guess you could say. Gave a lot of money to, um, offbeat causes—”

Adrienne laughed. “You can say it. Crazy la-la flower child. It’s not like I haven’t heard it before. She did support a lot of charities that other people wouldn’t. She was ‘unconventional’ — that’s the term my dad’s mother used. And she and Dad did love each other. Yes. Very much.”

“I didn’t mean—”

“It’s all right. Really. She came across as a lightweight to a lot of people. A flake. Everybody thought she was a gold-digger. Or would have been, they said, if she’d been able to focus on anything, including gold-digging. She’d cast some kind of spell over Dad, people said. Must be physical, they said. Why else would someone like him be the least bit interested in someone like her?”

“But—”

“Shush. Let me finish. Here’s what he saw in her: she was brilliant. I kid you not. Everybody knows about the foundations she set up, the donations she made — no strings attached — to fake yogis and spiritualist conmen. But almost nobody knows about the research she funded.”

Dolly Burghar a supporter of science? Gabe could not imagine a less likely pairing of needs and resources. Real science seemed antithetical to all the crazy stuff she’d definitely propped up: astral-projection mentalists, ESP nuts, tinfoil-hat conspiracy theorists obsessed with government mind-control rays…

“I don’t blame you for being skeptical. I really don’t. You’ll just have to trust me on this for now: my father lusted first after her mind. And I completely understood why, even before I knew what the word ‘lust’ meant. It all started with the monkeys.”

“Monkeys?”

She nodded. “Monkeys. When I was seven — yes, the same year Dad gave me my MagBurg badge — Mom gave me this toy. A game, really. At first I thought it was stupid, a toy for a, ha!, a little kid, you know? It had a bunch of parts, all of them identical. They came in a little plastic barrel, or maybe an oil drum. You didn’t really use that during the game, though. All the other pieces were these flat plastic stylized monkeys. One arm curled up, one arm curled down, and the legs were also cocked at interesting angles—”

She nodded. “Monkeys. When I was seven — yes, the same year Dad gave me my MagBurg badge — Mom gave me this toy. A game, really. At first I thought it was stupid, a toy for a, ha!, a little kid, you know? It had a bunch of parts, all of them identical. They came in a little plastic barrel, or maybe an oil drum. You didn’t really use that during the game, though. All the other pieces were these flat plastic stylized monkeys. One arm curled up, one arm curled down, and the legs were also cocked at interesting angles—”

“I think I saw one of those once,” Gabe said. “In an antique store, years ago. Had maybe a half-dozen monkeys, bright colors, right?”

“Hope you didn’t buy that,” Eldon said. “They’re supposed to come with a dozen monkeys in each barrel.”

Adrienne again: “Right. And the sets came in different colors. The barrel and the monkeys would all be red, or all green, or blue or yellow.”

“Okay. So I know the toy. Game, whatever. What’s the big deal?”

“Two things,” she said. “First, the way you play. You pick up a monkey off the table. You hold it over the pile of monkeys, and hook another monkey to it. Link the left arm of one monkey to the left of another, or to the right arm or a leg, keep the chain flat or twist it a little. And then you keep going, making these long, long chains. The winner is the person who makes the longest chain before they all fall off.

“And the second thing — the big thing, the brilliant thing — my mother did on her own, just for me: the barrel wasn’t a single color, but a rainbow of all four colors. It was twice the size of a regular barrel-of-monkeys barrel. And it contained four complete sets of monkeys: twelve red, twelve blue, and so on.”

Gabe tried and failed to get the magic which Adrienne seemed to ascribe to this picture. He looked to Eldon for help.

“Mathematics,” Eldon said. “Also physics, and chemistry, and genetics. All in the barrel of monkeys. Given the original set — a dozen same-colored monkeys — you could hook a single pair of monkeys together in any of eighty different ways. How many possible ways do you think there are to link a dozen monkeys together?”

“Uh — a lot.”

“Right. Now quadruple the number of monkeys, using four different colored sets—”

“A lot more. I get it.”

“They actually start to resemble chains of proteins, and polymers—”

Adrienne chimed in. “El. Stop. None of that matters. All that matters is the notion: a single pair of monkeys can be hooked up dozens of ways. Mom introduced me to that. And that’s been behind my whole adult life. Watch.”

She touched the black plastic disk. Again, a black sphere ballooned over it. But this one contained no stars, no galaxies, no on-again-off-again black something off to the side. Floating in the middle of the sphere glowed a bright-yellow word, in an odd font:

place

The letters didn’t just have serifs at the usual points, at the ends of the strokes. Serifs studded each letter here and there, and some letters had notches — inverse serifs — incised into their edges. As Gabe watched, Adrienne raised a forefinger to the bottom left edge of the black sphere, from her angle, and flicked it gently up and to the right. Another word swam into view, moving toward the center:

this

As it bumped into the word place, the this hooked somehow onto it with a nearly inaudible click, forming a misaligned word pair:

this place

The phrase drifted a little to the right, swung back to the left, spun slightly on its axis and back again as Gabe watched, nearly hypnotized.

Adrienne denied that he was observing a pair of words. “It’s a pair of ideas,” she said. “The words just represent the ideas of, well, specificity and position. And just like with the barrel of monkeys, you can build up these magnificent, complex structures out of almost nothing at all.”

Adrienne denied that he was observing a pair of words. “It’s a pair of ideas,” she said. “The words just represent the ideas of, well, specificity and position. And just like with the barrel of monkeys, you can build up these magnificent, complex structures out of almost nothing at all.”

“And that’s why we want you,” said Eldon. “A photographer, in your case. An artist. Someone who’s accustomed to hooking ideas together in new ways.”

“We… we called in some favors,” Adrienne said. “We know about the books you read, the music you listen to, the museums you frequent. You don’t buy or borrow material that has anything to do with photography.”

“Ha, an understatement. Everything but photography,” Eldon said. “Fiction, classic and modern. History. Poetry. Physics. Fifteenth-century Flemish painters. Information science—”

Gabe wasn’t about to fall for what sounded suspiciously like flattery. “Well, all right, but I’m no brilliant mind, no genius. Just a packrat. The only thing I’m halfway talented at is photography. Portraits, still lifes, landscapes. Fine. I still don’t get it.”

“We had some other criteria,” Adrienne said. “The ideal candidate needed to live near us. They needed to be, well, free of a relationship. They needed to be in a reasonably narrow age range — thirty-five to thirty-eight, plus or minus. And they needed to have a history of demonstrated, passive altruism.”

“We didn’t want an activist, in other words.”

“Right. Someone who’d donated here and there to noble charitable causes would be just right. But not someone who might—”

“—might try too hard,” Eldon summed up.

“So. Me,” Gabe said.

Adrienne nodded. “You. And three others. But you were the best match. The one we wanted.”

“To” — he looked down at Eldon, expecting to trigger another laugh — “to save the world?”

Eldon smiled, acknowledging the attempt at humor, but didn’t laugh this time. “To save the world’s ideas,” he said. “All the ideas linked together that make up, oh, say, every one of your photos.”

“All the world’s art,” Adrienne added. “And Shakespeare.”

“The films of Martin Scorsese—”

“—and John Waters. The old US Constitution. All the ideas that taken together, make up the Sistine Chapel.”

“Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. ‘Norwegian Wood.’ And ClearMouse’s Unfinished Rapera for Woodwinds.”

“You get the idea,” said Adrienne. “We want you to save it all. All the links, all the structures of links. If this works, Gabe, you and you alone will survive Kali. Everybody and everything else gone. No books. No music. No statues. But the ideas behind them all, ah: you’ll take all those ideas with you.”

__________________________

For nearly all the images in this post, I’m indebted to “Monkeys Ape Molecules,” an exhibit at London’s MRC National Institute for Medical Research. If you follow that link, and are interested in math, science, and, well, monkeys, be sure to check the links in its left sidebar as well.

__________________________

[Previous Chapter] [Table of Contents/Overview] [Next Chapter]

Jayne says

Norwegian Wood. Ha, I would have thrown that in there, too. ;)

Every once in a while, as I’m cleaning the basement or family room, or even the kids’ bedrooms (which, theoretically, I’m not supposed to be doing), I will find one of those monkeys on the floor, under the bed, or on top of a TV or sticking out of a baseboard. I throw them in a woven basket for odds and ends. Hmm… maybe I should change that habit.

John says

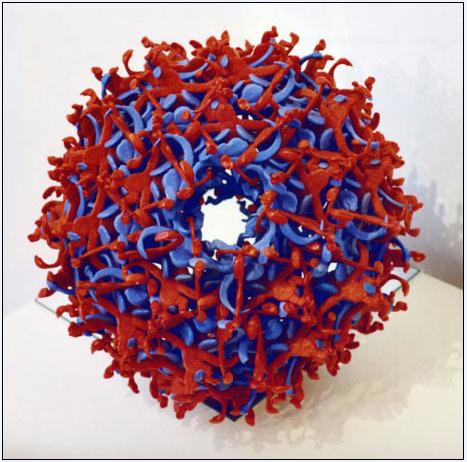

When I was working on this chapter, I knew instinctively that I wanted to use the monkey-things… even though I’d never owned or even played with them myself but just knew of them. I was delighted to find an entry for them in Wikipedia, and the more I read about them the more their complexity-in-simplicity impressed me. (I wonder if even their inventors knew what they’d wrought.) At that “Monkeys Ape Molecules” site I found so many images I wanted to use… one of the ones I (obviously :)) didn’t use was this one, called “Simian Virus”:

Its caption reads:

An entertaining bit of reading — if you’re as easily entertained as I am, anyhow — is the 1965 patent filing, by one Leonard Marks, which begins:

Yikes. So that’s what an idea looks like.

zac says

Hi John, the website you listed is no longer reachable, is it possible to find documentation of this exhibition elsewhere?

John says

Zac: thanks for the heads-up! I found it at the Internet Archive’s Wayback site:

https://web.archive.org/web/20070211150151/http://www.nimr.mrc.ac.uk/monkey_molecules/

Thanks for stopping by!

s.o.m.e. one's brudder says

Let me know how many different versions of “monkeys” you want…I’ll try to accommodate.

John says

I’m not sure what exactly you’re offering there. But I should tell you that if it’s going to involve the shipment of any sort of trinkets thisaway, well — the fewer, the better.

The Querulous Squirrel says

The idea of one person housing all the world’s ideas for posterity in one brain is very sad. Each brain is different. Every perception is subjective. The idea of Kali from ancient India recurring in the future to erase what happened in between is much scarier than the arrival of aliens.

John says

One of the story’s loose ends which I picked up on almost immediately — which I want to correct — is the suggestion that this might actually be the Kali. As I imagine it, though, this Kali has just been so named by Eldon Lane in metaphoric reference to the legend.

It might help to swallow the “idea of one person housing all the world’s ideas for posterity” if you remember that Gabe will not have a brain, as such. The cloud of ideas can essentially be boundless. And I think that you and I might be referring to two slightly different things when we talk about ideas… which I hope will be plainer after a couple more installments.